The word “prosocial” refers to any belief, attitude, or organization that is oriented toward the welfare of others or society as a whole. ProSocial World is an organization dedicated to making the world more prosocial. Although ProSocial World is our formal name, we often shorten it to ProSocial as our nickname.

Many, many organizations have a prosocial orientation, so the big question for all of them is how they can achieve their objectives. ProSocial is distinctive in two ways. First, it is based on the latest advances in evolutionary science. Second, we have packaged these advances into a very practical set of tools for working with single groups, multi-group “cultural ecosystems”, and ultimately at the global scale.

Calling ProSocial an “organization” requires a bit of unpacking. It started ten years ago as a project of the Evolution Institute, which is a nonprofit 501 (c) 3 organization. Currently, it exists as a values-driven non-profit organization with the Prosocial Institute as its training arm. But these two entities don’t fully capture what we mean by organization. Instead, we mean the worldwide community of scientists, trained facilitators, and groups that work together to make the world a more prosocial place. This community needs to be activated, but that activation cannot take the form of any single or even small collection of nonprofit and for-profit entities. Instead, it might need to be more like the communities that have formed around open-source software development, a point to which I will return below.

The development of ProSocial up to this point can crudely be described as three stages. ProSocial 1.0 brought together the major pieces of our practical method. ProSocial 2.0 attempted to scale up the method and included some successes but also some very instructive failures. ProSocial 3.0 is poised to do a better job working at the “Micro”, “Meso”, and “Macro” scales worldwide.

ProSocial 1.0

The origin of ProSocial is described in a separate blog post. Essentially, it was a fusion of two collaborations. The first was with the political scientist Elinor Ostrom, who received the Nobel prize in economics in 2009 for showing that groups can manage natural resources such as forests, pastures, and fisheries, avoiding the famous “tragedy of the commons”, if they implement certain core design principles (CDPs). I met Lin shortly before she received the prize and worked with her for three years prior to her death in 2012. The main import of our collaboration was to show that almost all groups need the core design principles, which are basic for cooperation in all its forms, along with auxiliary design principles needed by some groups but not others to accomplish their particular objectives.

The other collaboration was with Steve Hayes, Tony Biglan, and Dennis Embry, who described themselves as Contextual Behavioral Scientists (CBS). This is an umbrella term for the study of human behavior in the context of everyday life, with the goal of prediction and influence in addition to basic scientific understanding. It includes an amalgam of applied disciplines such as Pragmatism (the tradition of William James and John Dewey), Behaviorism (the tradition of B.F. Skinner), Cognitive and Mindfulness-based therapies (which Steve Hayes synthesized as Acceptance and Commitment Training, or ACT), Prevention Science and Public Health (which work at the scale of populations). The bottom line is that CBS has an impressive track record accomplishing positive change at multiple scales (e.g, individuals, small groups, and large populations). Yet, its various sub-disciplines are poorly integrated with each other or with the so-called basic (as opposed to applied) sciences.

That’s where evolutionary theory enters the picture. It already functions as a unifying theoretical framework in the biological sciences and can do the same for all of the basic and applied human-related sciences. This is the objective of all of my work, most recently summarized in my book This View of Life: Completing the Darwinian Revolution. What the whole world needs to know is that evolution is not restricted to genetic evolution. It also includes all of the fast-paced changes taking place around us (cultural evolution) and even within us (our personal evolution). Yet, evolution doesn’t make everything nice. If often results in behaviors that benefit me but not you, us but not them, or our short-term but not our long-term welfare. This means that work is required to align evolutionary processes with our normative goals. Positive change efforts in all of their forms can be seen as the wise management of evolutionary processes.

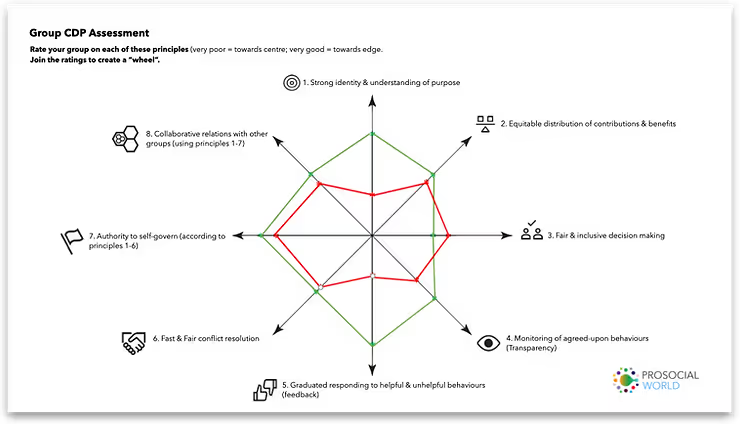

Against this background, ProSocial emerged as a practical effort to accomplish positive change in three steps: 1) Increasing the capacity for individuals and groups to change in valued directions (the CBS piece); 2) Learning about and adopting the core design principles required for groups to function as cooperative units (the Ostrom piece); and 3) the formulation of short term goals that take groups in the direction of their long term goals.

ProSocial 2.0

Pilot funding for creating a practical framework came from the Cooperative Group of the UK, a consortium of business cooperatives that began in the 19th century and is still going strong. A steering committee formed that was drawn largely from the Association for Contextual Behavioral Science (ACBS), which Steve Hayes helped to create and now includes over 8000 members worldwide. This illustrates the important point that the best way to grow ProSocial is with the help of existing social networks.

Early on, we decided to use a particular form of ACT called the Matrix, although we remain flexible about employing other methods for the first step of ProSocial. Since the first step is all about flexibility, we must be flexible as well! However, the Matrix is proving to be a powerful tool, as numerous articles and video case reports on the prosocial.world website attest.

An early milestone was a training manual and an effort to organize a group of facilitators on Meetup.com. That resulted in a small number of facilitators working with us to implement ProSocial but fell far short of our ambitions. Then the New Harbinger publishing company and its affiliate organization Praxis, which already worked closely with ACBS, offered to help us develop our own website. Initially, we imagined something that groups could access without requiring a facilitator. Unfortunately, that project proved to be too ambitious and had to be abandoned. It was a good learning experience, however, and convinced us that we needed to build a system of trained facilitators to work with groups. Providing tools directly to groups would not be good enough.

It has always been part of the vision of ProSocial to score high on assessment methods and to conduct basic scientific research in real-world settings. After all, the way that Elinor Ostrom derived the core design principles was by creating a database of common-pool resource groups around the world, mostly from the literature rather than interacting directly with the groups. We can go even further by creating a database of the groups with whom we are actively working. It will be a grand experiment in cultural evolution, conducted in partnership with the groups themselves, in the spirit of Participatory Action Research. We proceeded to lay the groundwork for such a database, even if we didn’t yet have the resources to implement it. We also began to ramp up our capacity to train facilitators, with Paul Atkins playing a leadership role.

In addition to these planned activities, a number of people from the ACBS community began to pick up the ProSocial ball and run with it on their own. In a way this was disconcerting because it lacked the coordination that is part of our vision. It was also gratifying, however, because the people adopting ProSocial were already highly trained and accomplished at working with groups. This meant that in their estimation, ProSocial was adding something to their existing toolkit of change methods.

This prosocial.world blog includes a growing number of articles, interviews, and video case reports of ProSocial implementations in this “disorganized” phase of our development. I especially recommend the interviews with Robert Styles [1,2] for two reasons. First, he is especially detailed and articulate about how he works with large organizations (government agencies) with challenging problems. Second, his assessments are exceptionally comprehensive, thanks to the fact that all Australian civil employees take an annual survey, enabling a comparison of the agencies that Robert works with and all other agencies.

Other blog posts paint a remarkable portrait of a practical method that can work in any culture and context. Beate Ebert and Donna Read have worked in Africa to address the Ebola epidemic, domestic violence, and community development. Beate also worked with her husband’s dental practice in Germany. Jim Lemon has worked with a pediatric healthcare system in Scotland and Stuart Libman has worked with an organization serving learning-disabled children in America. Jeff Genung is exploring the role that spirituality plays in animating prosociality in groups in Texas and elsewhere. Business groups need ProSocial as much as any other kind of group—and we have the numbers to prove it*.

While numbers are important, the video case reports produced by Alan Honick, a member of the ProSocial development team who is also a documentary filmmaker, provide a richness that numbers can’t convey. Several themes emerge from the facilitators and group members talking about their experience. First, ProSocial works fast. This is where the Matrix proves its worth as an exceptionally rapid method for helping individuals and groups become more flexible working around obstacles to achieve their valued goals. Second, Prosocial becomes second nature. Once learned, the Matrix and the CDPs are employed on a daily basis as the group works to accomplish its objectives. Third, ProSocial spreads virally. People who learn about it in the context of one group spontaneously apply it to other groups in their life. If ProSocial has been this successful in the hands of facilitators working relatively independently of each other, imagine what is possible with more organization of the right kind!

ProSocial 3.0

The current phase of ProSocial’s development began with a grant from the Templeton World Charity Foundation in July 2018. Now at last we had resources to begin realizing the worldwide framework that we always had in mind. The structure that we have created during the first year of the grant includes the following elements, which are described in more detail in other sections of the prosocial.world website.

-- A system for training ProSocial facilitators. Paul Atkins teaches a six-week online course on a regular basis, resulting in a community of over 200 graduates around the world. Our plans call for additional instructors to be trained, for basic training to take place in different languages, for advanced courses to be taught, and for training to take place in workshop settings in addition to online.

-- Tools for facilitators to work with their groups. The ProSocial ARC Process is the process that group members go through with their facilitator. It includes all of the assessment measures that contribute to our scientific database and result in beautiful automatic reports to be shared with group members. It also includes an online version of the Matrix that can be used directly or can receive input after the fact when it is more appropriate to use the Matrix offline. From the perspective of a group, the ProSocial ARC Process provides an exceptionally well-organized way to step through ProSocial. From the perspective of the facilitator, it provides a way to easily work with multiple groups, simply by cloning the material for each new group. From the standpoint of the ProSocial Development Team, it provides a way to capture the same information from each group for its multi-group database.

-- Tools for ProSocial facilitators and their groups to work with each other and the ProSocial research community. This virtual community is a work in progress and currently includes a “Find a Facilitator” section of the prosocial.world website and a community site for discussion and sharing of best practices. The goal is to strike the right balance between autonomy, enabling each facilitator to take ownership of his or her development of ProSocial, and community, enabling ProSocial facilitators to learn from and enable each other.

Micro, Meso, Macro

ProSocial is most advanced in the tools that it has developed for working with single groups, which we call the “Micro” scale. It is important to emphasize that our Micro scale is the group, not the individual person. This is one of the most distinctive features of ProSocial, compared to other change methods and theoretical frameworks, which treat the individual person as the “micro” unit and often fail to recognize the importance of (typically) small functionally oriented groups at all.

It is also part of our vision to work with multi-group cultural ecosystems, which we call the “Meso” scale. This might be a business group and its supply chain, a political unit that is convenient to work with such as a city or county, or a natural biological unit such as a watershed. In all cases, we plan to train teams of facilitators working with groups both to improve their internal social organization (CDPs 1-6) and their relationship with other groups (CDPs 7-8). This is conceptually straightforward because the core design principles are scale independent. In other words, the Meso unit must acquire an identity and purpose (CDP1), what groups get from interacting with other groups must be proportional to what they give (CDP2), all groups much participate in decision-making, and so on. We will be working to develop tools to establish prosocialilty at the Meso scale in addition to the Macro scale.

The Macro scale is the welfare of the whole earth. Not only is this the ultimate scale of implementation that we are working toward, but it informs the values and objectives of working at all scales. In other words, what we do at any given scale must be part of the solution rather than part of the problem at higher scales. Many people who are drawn to ProSocial already have a whole earth ethic, but evolutionary theory, appropriately understood, provides a scientific justification for it that needs to become more widely appreciated.

Learning from Open Source Software Development

What is the best organization for catalyzing the spread of ProSocial around the world? Conventional thinking would steer us in the direction of nonprofit and for-profit organizations, alone or in combination. The concept of “open source”, which originated in the world of software development but has broader relevance, is worth considering as an alternative. In open source software development, the code is not owned by anyone. Intriguingly, it is a common-pool resource that anyone can use and improve. A vibrant community of developers forms that collectively is much more creative than any single company that attempts to make a profit from its software. This is how the Linux operating system successfully competes against Microsoft and even wins over other giant corporations such as IBM. Also, plenty of people and organizations make a good living from open source software development, such as Red Hat, which markets open-source software products that could be duplicated in principle, but that few people would want to duplicate in practice. A good book on the subject is The Success of Open Source by Steven Weber.

We don’t know exactly how ProSocial will develop in the future. It will be a cultural evolutionary process that cannot be predicted in advance. However, we are attracted by the open source concept, which appears to combine the best of individual autonomy and initiative with the best of community. In this spirit, we encourage our facilitators, researchers, and groups to develop Prosocial as they see fit, in a way that contributes to the collective goal of making the world a better place.

It will be fascinating to see what form ProSocial 4.0 takes.